Illiterate Landscape questions the tradition of landscape painting in China on issues of space, perspective and light.

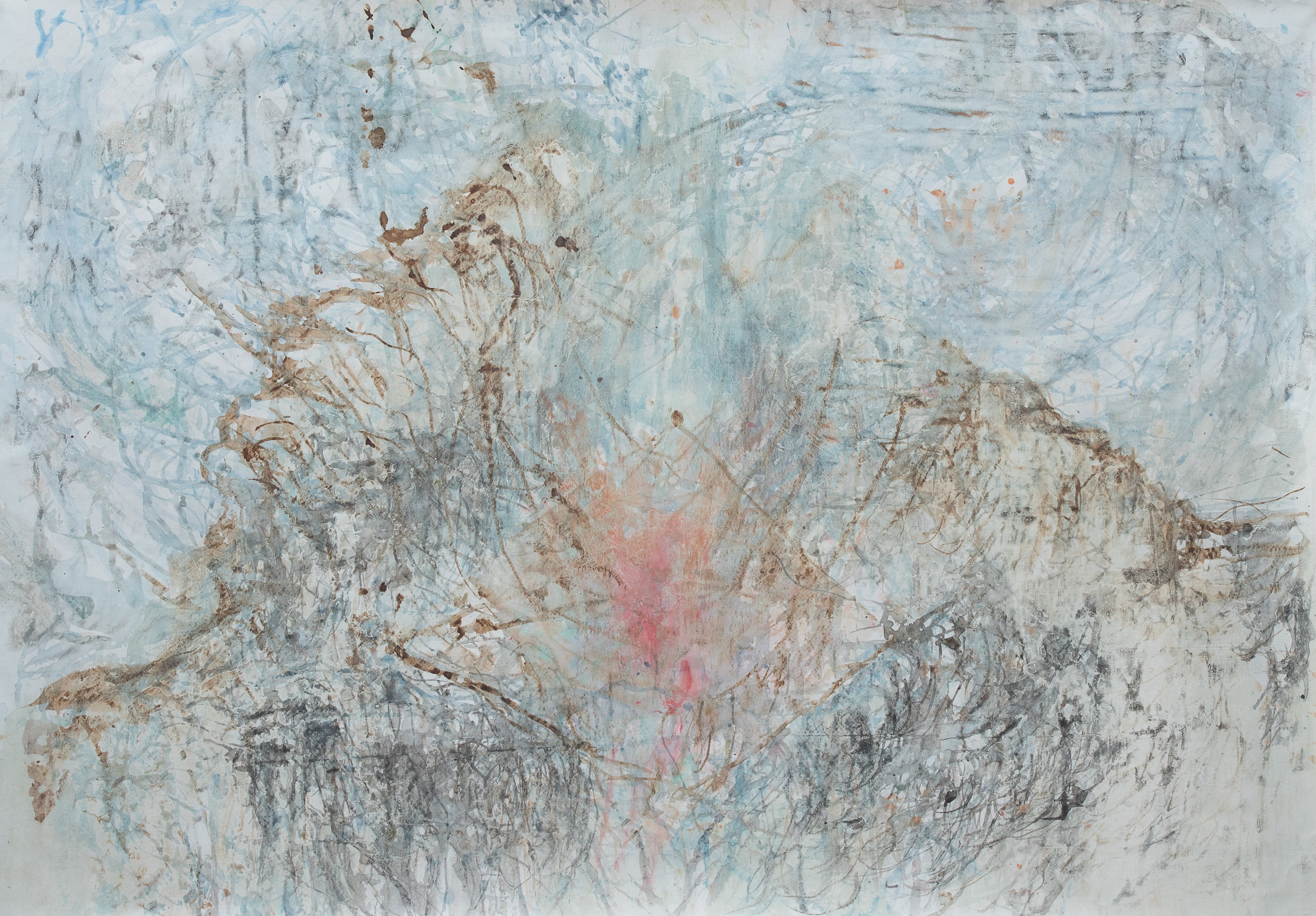

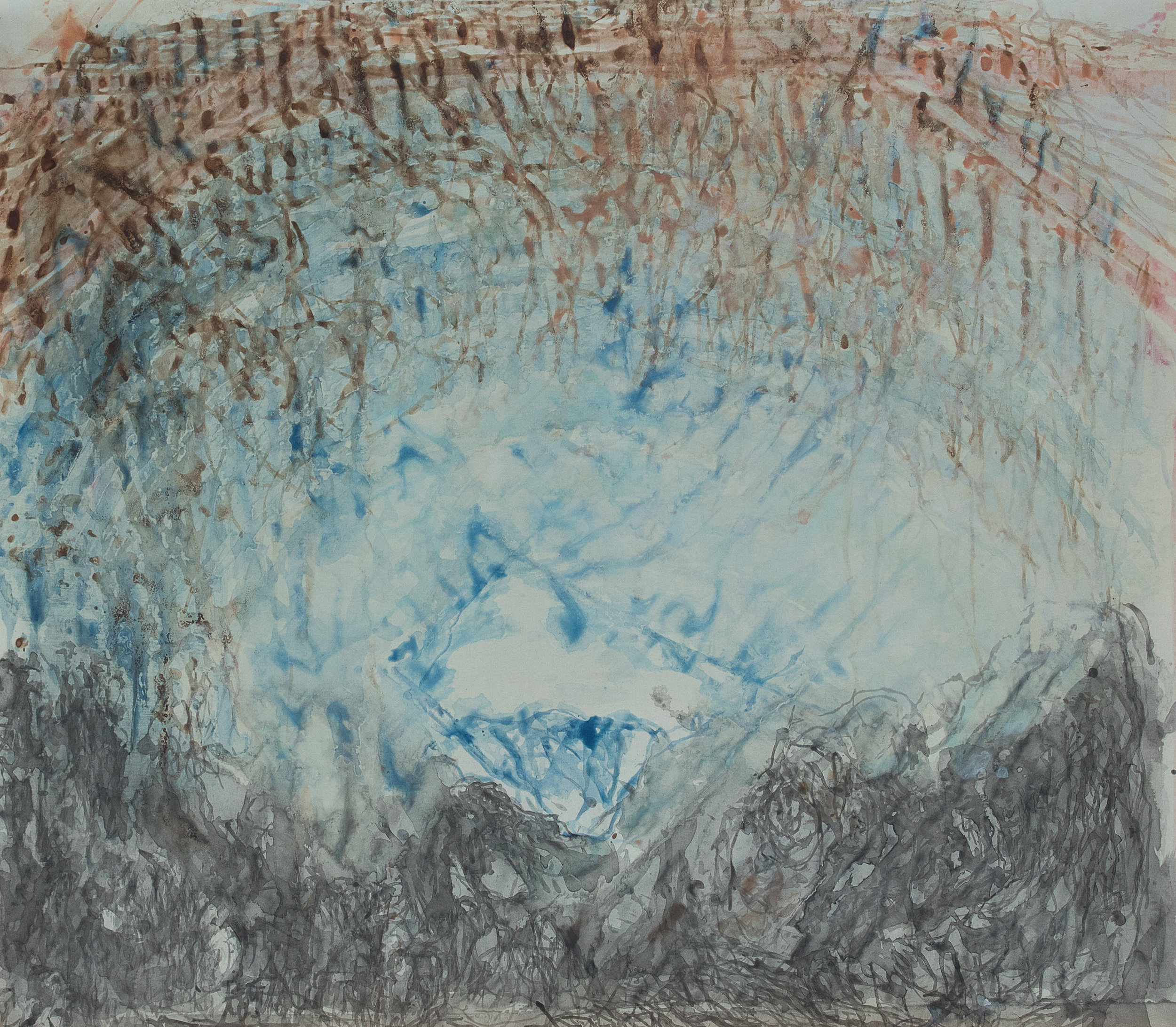

Illiterate Landscape revisits the materiality of Chinese landscape painting in terms of pigments, support and brushwork. Pigments are directly sought for in the mountains of Southwest (reds, purples, indigo) and Northeast China (greens and ocre), while some colours unknown to Chinese painting are introduced (walnut stain).

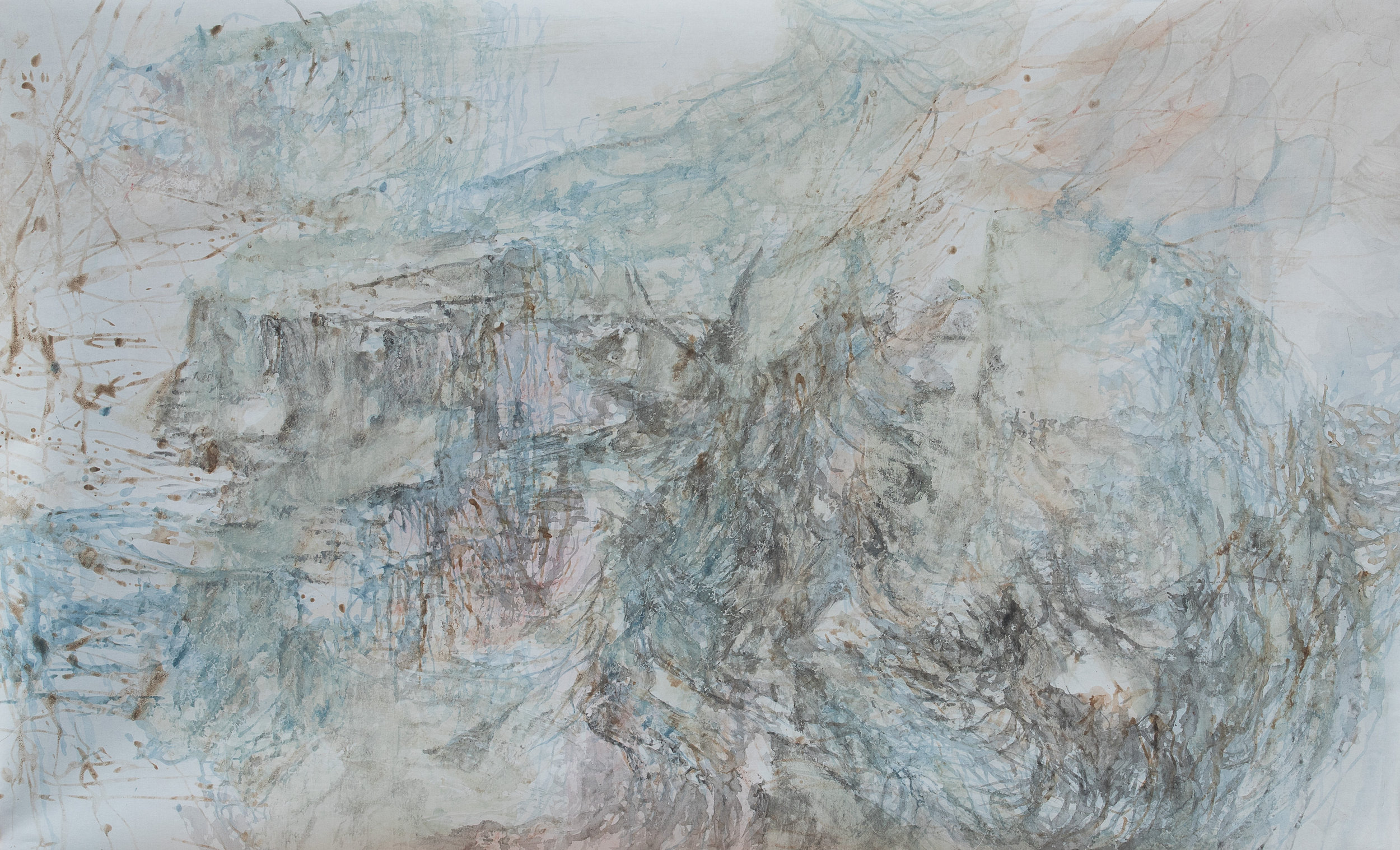

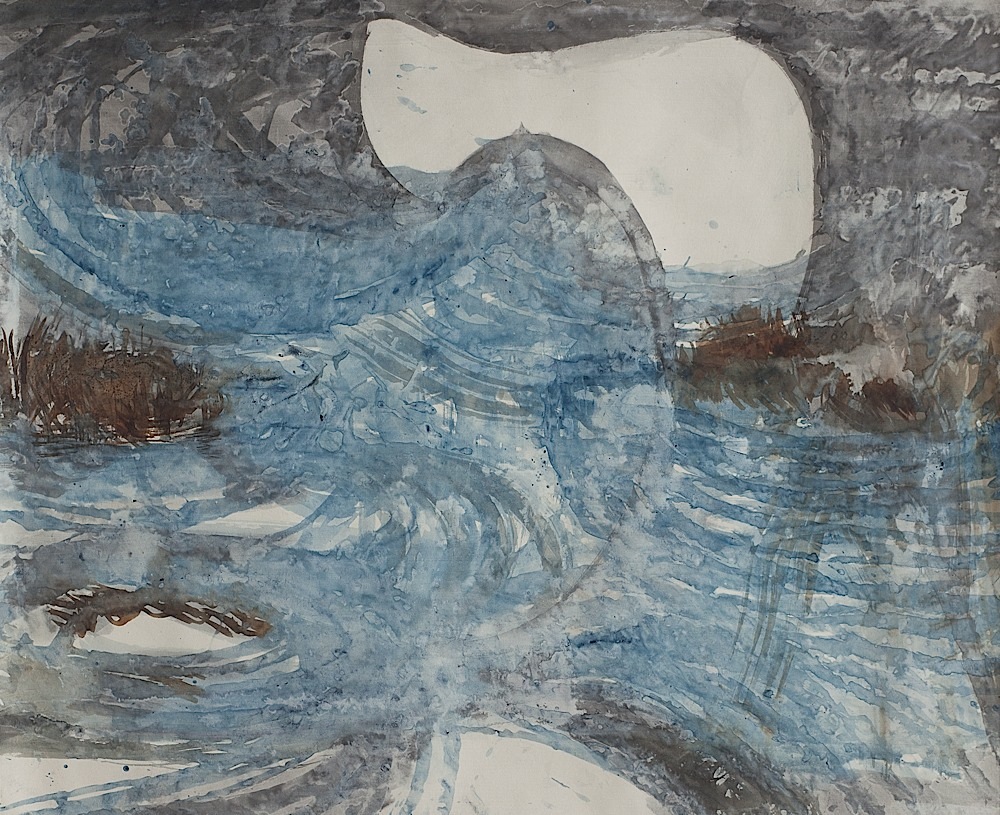

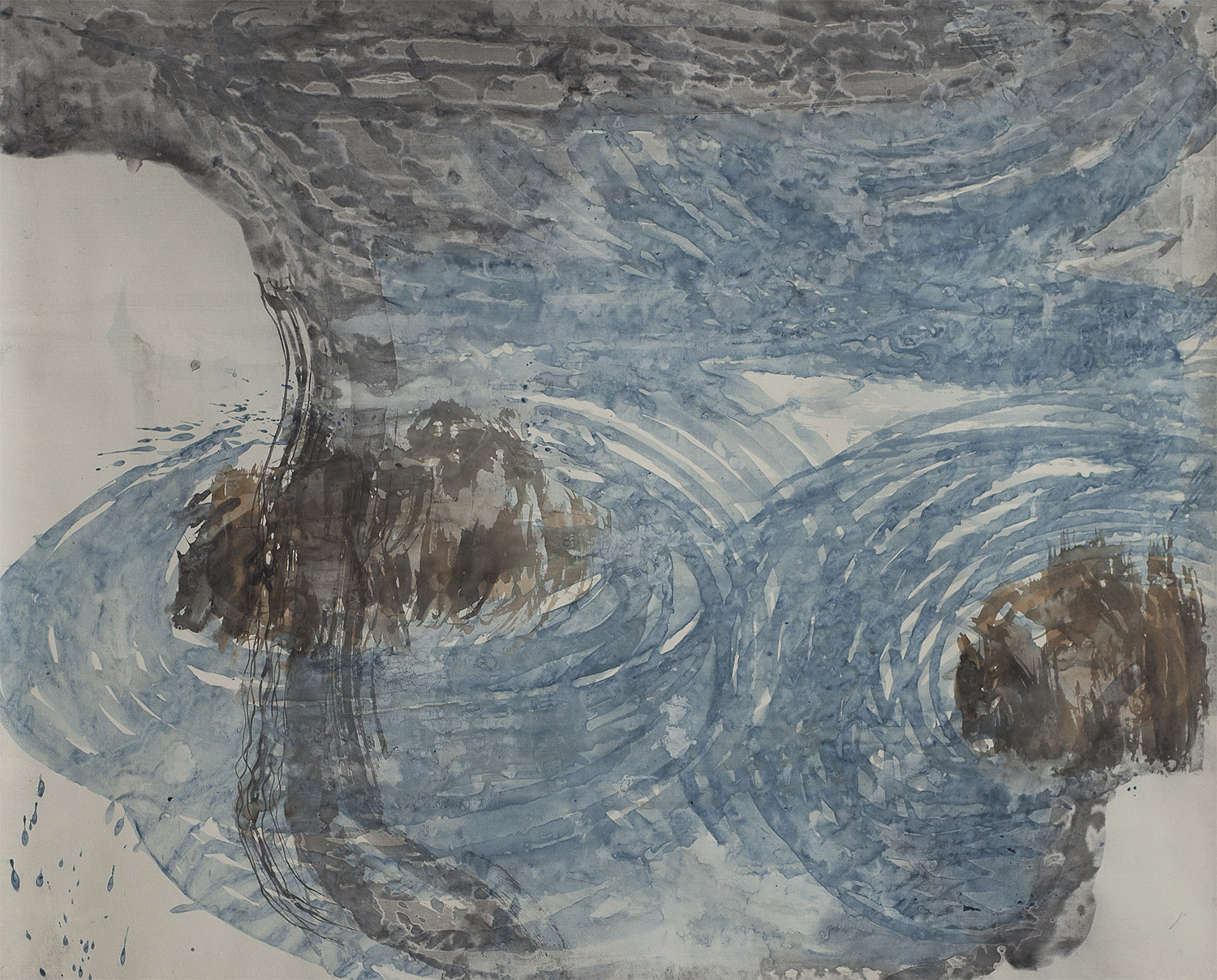

Silk is preferred to paper for its resilience and transparency, which allow superimpositions and a more lavish use of thick-grained earths or minerals and glues. Brushstrokes are willingly broken, avoiding the disciplined effects of calligraphic lines.

Illiterate Landscape also strips Chinese landscape painting of a number of its constitutive elements. Calligraphy and seal impressions are banned from the painted surface, so that landscapes stand alone, divorced from the traditional toolkit of literati art. The usual elements determining scale and readability present in traditional landscape painting, such as architectural elements, tree or human figure, are omitted. Thereby, the landscape avoid being attributed a scale and the eye is left with no guide to roam the peaks and ravines.

Illiterate Landscape focus on issues of spatial articulation, composite perspective and the idea of a visual itinerary. Chinese landscapes are made out of loosely related scenes often referred to as ‘space cells’, with clouds, mist, vegetation or water serving as transitions. While the wider structure of the landscape can suggests general movements of ascension or horizontal travelling, the viewer’s eye is left relatively free as to how to articulate its itinerary from one space cell to another.

Zonal textures, smooth transitions and principles of classic compositions encountered in Chinese landscape painting are present in a fragmentary, recombined state, inviting the viewer to wander along discontinuous lines.